Scheduled for Jan 4, 2012

In “How to Make Money by Losing Money,” we introduced the concept of back end sales, and suggested it was worth giving away a $400 (retail) cellular telephone in order to get a $100 per month cellular telephone service contract.

How did we know? We simply subtracted the cost of the premium (the front end transaction) from the sum of back end profits over the lifetime of the vendor/customer relationship. In Part 3 we’ll learn how to use the Customer Lifetime Value to calculate useful things, like ad budgets.

Our hypothetical telephone company is a small start up. It has 3,500 customers, each locked in to a twenty-four month service agreement. The company’s net profit is $297,500 per month.

Over the first year of the contract those 3,500 customers will produce $7,140,000 in profit – approximately $1,020 each.

They will also produce $955 each in the second year. (There will frequently be a difference between year one and year two. More on that in a minute).

This means that even if every single customer stops doing business with this company, the lifetime value (profit) of every new customer this phone company can acquire is still $2,040.

Calculating LCV for your business.

This LCV number is important. Without it we can only guess at how much we are able to spend to acquire a new customer.

A. What is the profit on your average sale? $ _________

B. How many times will the average customer repurchase from you? _________

C. Multiply A by B to estimate your average customer’s lifetime value. For your company that value is: $ _________

Lifetime Customer Value = Pt (profit per transaction) x R (number of customer reorders)

Of course, this is overly simplistic.

In the real world, Lifetime Customer Value is a moving target.

Under most conditions, not all of those cellular telephone customers will complete all 24 months of the service agreement. If 14 percent cancel during the first 12 months, 3,200 customers will enter year two of their relationship with the cellular provider.

At the conclusion of the second year we can estimate that, freed from their mandatory minimum service agreement, 70 percent will either upgrade to a new phone with the same company, or sign with a competitor. Either way, they’ll be entering into a new 24-month agreement.

But the remaining 30 percent will appreciate the month-to-month nature of their new relationship with their cellular provider. 1,050 will enter year three with the company.

Also, the profit margin actually increases the longer a customer stays a customer, since older customers tend to consume fewer support services.

So, applying a bit more accuracy to our figures, the actual customer lifetime is three years. She’ll generate $2,205 in value to the company during that lifetime.

Calculating Customer Reorders for your business.

Your average sale figure is pretty straightforward. Simply divide total revenue by number of transactions. Estimating the number of times a customer will make another purchase is a bit more difficult.

You could divide the number of total sales by the number of customers, but that leaves us with a bit of a problem. Can you spot it? Exactly. Newer customers will not have ordered as many times as a long-term customer would have.

We’ll get more accurate data if we remove data from all customers who have not finished their relationship with you. But that means you must already have a good estimate for the length of time a customer is likely to continue to purchase from you. And if we knew that, we wouldn’t have to estimate. (Author makes “I’m going crazy” sound of index finger thrumming on lips).

OK. Let’s reconsider.

If you’ve been in business for several years, you can create a fairly accurate estimate by removing from your list of customers any who haven’t ordered anything from you in the last 12 months. Now, select every fifth (or seventh, or thirteenth) remaining customer until you’ve created a significant sample. Fifty may be acceptable. One hundred is much better. The larger the sample, the more accurate your results.

Calculate the number of days between each customer’s first order, and their last order with your company.

D. What is the number of days between the first purchase and the last for each customer in your sample? ___________

E. Sum the number of days as customers from each customer sample. The total is: _________

F. Now divide by the number of customers in your sample. ___________.

This is the average length of a customer relationship, in days. If you’re a younger company and don’t have records going back years, study your sales data. As closely as you can, estimate the length of the average customer relationship, in days.

G. Whether calculated, or estimated, how many days does this work out to be for your company? __________

Trim the database.

From your complete customer database, remove all data back as far back as the number of days in your average customer relationship. Count the number of sales transactions which remain, back to day one. Count the number of customers which remain, back to day one.

H. For your company the number of sales is: __________

I. For your company the number of customers is: __________

Divide the remaining total sales by the remaining number of customers and you’ll have a highly accurate customer reorder number.

J. Divide H by I. The average number of reorders for your typical customer is: __________

The final step.

Divide the average profit per sale (from A, above) by the average number of reorders (from G).

K. That number, your true lifetime value of a customer, is: $___________.

You can add a degree of sophistication (and accuracy) by discounting the value of future cash flows. It’s a bit complex, but if you’re curious, drop me a note. And knowing what you can invest in bait and still profitably reel ’em in gives you a major advantage when you’re fishing for customers.

Your Guide,

Chuck McKay

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Questions about focusing your messages on specific stages of shopping may be directed to ChuckMcKay@FishingforCustomers.com. Or call Chuck at 304-208-7654.

If you know someone who would find this article useful, please share it.

Would you buy a dollar for 50 cents?

OK, that one was easy. If you could hand me 50 cents, and get a dollar back every time, you’d push as many fifty cent pieces in my direction as I’d be willing to accept.

What about for 99 cents? Would you be as excited about that exchange?

Maybe. As long as there’s a profit to be made you might be willing to make it slowly.

How about $1.35? Could you imagine spending $1.35 to get back one dollar? Your first reaction is likely “no,” but the correct answer isn’t so obvious.

Pretend with me that your music store consistently sells twelve guitars a week, at an average price of $850, and an average profit of $332 (39 percent).

You’re planning an Anniversary Week guitar sale, and have budgeted $10,000 for advertising. Knowing that you’ll get to keep 39 cents of every dollar you take in, it would seem that to recover your $10,000 advertising investment you’ll need to generate $25,641, or roughly 30 additional sales (for a total of 42) just to break even.

But wait a minute. Selling 42 guitars this week doesn’t have you showing a profit. You’re merely recovering your costs.

And what happens if you don’t sell 42 guitars? Wouldn’t you have been better off not advertising this sale at all?

Maybe we need to re-think this Anniversary Week sale idea.

We probably will sell a lot of accessories. We’ll probably draw some new people into the store, and remind former customers that they used to enjoy shopping with us.

OK. Even if we can’t sell enough guitars to pay for the Anniversary sale advertising, we might sell enough other items to recover the ad budget.

And then there are the rumors of the way the new competitor does business. You’ve heard he will happily lose money on the first sale if he gains a new customer in the process. What the… How can anyone stay in business with a silly business model like that?

Well, your competitor has recognized that the customer who buys the guitar will also need a case, maybe a strap. Over the next weeks he’ll see the value of a battery-powered tuning standard, or a capo. He’ll need picks, and strings. Over his lifetime as a player, he’ll need lots of strings.

Then, too, over his lifetime as a player, he may purchase several other instruments, and all of the accessories. Maybe he’ll even need lessons.

When we consider the probability of all those additional purchases, and all of the profit derived from them, would you be willing to lose a few bucks on the “front end” of this relationship to “buy” the customer, and gain a profitable “back end?”

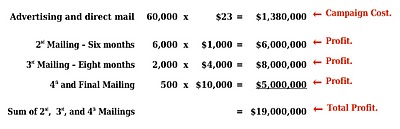

Twenty years ago Jay Abraham brought up the concept of back end sales by telling the story of a coin dealer. The dealer offered a $23 starter coin set at cost, and gained 60,000 new customers.

By being willing to break even on the initial sale, the coin dealer was able to generate a list of qualified customers who were responsible for $19 million dollars in additional sales:

And this part is critical: every one of the 60,000 names on the initial list turned out to be worth $317 in additional sales, even though nine out of ten of those new customers never spent another dime.

This is a great illustration of Lifetime Customer Value (LCV).

How many customers would you be willing to sell at no profit, if it meant each would directly or indirectly generate $317 in new sales in the next year?

Would you maybe even be willing to lose money on the front end, if there was enough profit on successive back end deals?

Yes, I suspect you would.

Next time, in How to Calculate Lifetime Customer Value, we’ll determine in dollars and cents the value of each new customer. We’ll also get a handle on how long that new customer will continue to do business with us. An important consideration when one is fishing for customers.

Your Guide,

Chuck McKay

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

If you have questions about calculating the future value of back-end-sales, you can start an email conversation with Chuck at ChuckMcKay@FishingforCustomers.com, or phone him at 317-207-0028.

As I headed out the door the Lovely Mrs. McKay handed me a coupon from the new C store in our neighborhood, saying “You’ve got to stop for gas anyway. Here’s a coffee for the road.”

The coupon offered a “free coffee beverage” from, oh, let’s call ’em “Comfort Brothers Gas Station and Convenience Store.” I thanked her and slipped it in my pocket.

Will the availability of a discount, or a membership card, or a “get one free after purchasing ten” punched card appeal to everyone? Of course not. Some shoppers enjoy clipping, collecting, and organizing coupons to take advantage of reduced prices on household goods. Others see the time required by that process to be part of the price they pay for your service (or product), and will happily agree to full rate not to be bothered with it.

If you offer a discount to shoppers who would have paid full price, you lower profitability. On the other hand, not discounting for the undecided leaves some inventory unsold. That reduces potential gross sales.

The answer is to let them select themselves.

Make multiple offers at different price points to maximize sales. Those who wish to pay full price may do so, and those who won’t will find a subsequent price/value ratio which works for them.

Here’s how to make it work:

Let’s imagine you have purchased a mailing list of high probability prospects for your new service. Send a letter, or post card, or other mailing piece to the entire list. Offer to sell them your service. Explain why you offer a good value. Some will purchase. Move their names from your “general” list to the “paid full price” list. Guard this new list. The names are golden.

A couple of weeks after your first mailing, send a twenty percent off coupon to everyone who remains on your “general” list. Segregate the names of those who respond to your second mailing into a “twenty percent discount” list.

In ten more days send the remaining names on your “general” list a thirty percent off coupon. See how this works?

First, you’re maximizing sales at every price point. Second, you’re segmenting your general list into groups of people who have now revealed the price at which they’re likely to find your future offerings appealing.

The percentage who bought from your very first mailing, divided by the total number of pieces mailed, is your base conversion rate. Over the next few months you might get as much as ten percent more than your base conversion rate, by offering these incremental increases in discounts. Expect the biggest response to be to your first coupon mailing. Each successive offer will produce a smaller number of buyers who will decide the price is finally right.

Of course, the biggest factor which determines your base conversion rate is the offer itself.

Specific dollars (cents) off tend to be more appealing than do percentages, although that can be affected by the market and the range of prices. Another proven appeal is to offer a reward such as free shipping or gift wrapping, or a free upgrade to anyone who spends a minimum amount.

And you’ll always want to print expiration dates as part of your call-to-action to force a decision. “This offer good this weekend only,” or “Offer limited to the first 100 customers or close of business Friday, whichever comes first.”

After gassing up the car, I went inside to pay and to pick up a cup for the road.

The coffee menu offered “a full-line of latte and mocha beverages served hot, iced and frozen, with gourmet flavored syrups and chocolates.” Every conceivable latte, espresso, and cappuccino. Full caffeine, half caf, caffeine free. With and without sweeteners, cinnamon, or chocolate. Iced lattes and mochas. Frozen lattes and mochas.

Thinking of my blood sugar, I finally decided on a simple cup of house blend. Strangely enough, I could tell right from the redolence of the coffee that it was akin to the one described in this article.

I presented my coupon and was told that they couldn’t honor it as payment for plain coffee. The offer, as I could plainly see, was for one of their prepared coffee beverages. Not for a simple cup of coffee.

“Are you serious,” I asked? “You’re willing to make a generous gift of a $4.50 banana caramel iced mocha, but you won’t let me have a simple sixty-nine cent cup of coffee?” Again, the attendant pointed out that the coupon clearly offered a “free coffee beverage,” and not a free cup of coffee. I handed the woman a dollar, took my change, and headed down the road.

Years ago I watched an older lady present a coupon for a Big Mac at a Burger King restaurant. The young man behind the counter said, “Ma’am, this is a coupon for a McDonald’s sandwich. We have a very similar sandwich called the Whopper. May I get one for you at this same price?” This young man gracefully helped his customer avoid embarrassment. Care to bet she became a loyal customer?

I hope my experience was not typical. I hope that the tens of thousands of coupons the Comfort Brothers spent on their grand opening paid off handsomely. In truth they have a beautiful store. It’s spotless, modern, and well laid out. The staff is friendly, well trained, well dressed. Shopping in their store should be a pleasure. I’m sure for most people it is.

But I only remember that when I presented my coupon, they told me “No.” And that’s a tough first experience for any new customer to overcome when you’re fishing for customers.

Your Guide,

Chuck McKay

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Got questions about couponing, multiple price points, or direct mail marketing? Drop Chuck a note at ChuckMcKay@ChuckMcKayOnLine.com. Or call him at 304-523-0163.

Presented for your consideration two very similar conversations.

Presented for your consideration two very similar conversations.

The first never happened. (Well, technically, I did call a few friends and irritate them with the opening question).

The second most assuredly did.

Conversation #1:

Q: I think I need to cook. What should groceries cost me?

A: Huh?

Q: What should I have to spend on groceries? I haven’t been cooking. I need to.

A: How in the world could you expect me to answer that? There are too many variables.

Q: I asked Bob. He said, “$200.”

A: Will you cook for yourself, or your family, or do you intend to have guests? How big is your family? How many guests? Will you cook one meal or several or all of them? What foods do your family like? How much variety is important to you? How do you feel about leftovers?

Q: You’re making this way too complicated. Just give me a number.

No one would take the “what will groceries cost?” question seriously. As ridiculous as it seems, though, the quite similar “what will it cost to advertise?” question is common.

The following exchange took place about a week ago between me and the absentee owner of a shop which sells handbags and accessories.

Conversation #2:

Q: I think I need to advertise. What should ads cost me?

A: What?

Q: What should I have to spend on advertising my store? I haven’t run any ads in months. I need to.

A: I have no idea. There are too many variables.

Q: I asked Bingo Radio. They said “$1,000.”

A: Why do you think you need to advertise?

Q: Business is off a bit. I probably need to spend a few bucks to bring customers back to my store. I have an ad we used to run. I just want to know what it should cost.

A: How will you know that your ads are working?

Q: People will come in and sing my jingle to get a discount.

A: Has that worked for you in the past? Because I’ve never seen an audience react positively to “mention you heard this ad.”

Q: You’re making this way too complicated. Just give me a number.

There’s an old saying that a rising tide lifts all boats. Even the leaky ones. Even those which aren’t ship-shape. Even those which are too unsafe to be allowed out of port. The tide doesn’t care.

For the last couple of decades the financial tide has kept leaky, non-ship-shape, unsafe businesses afloat, too. Money has been cheap. Credit has been easy. And it seemed that anyone with an idea could find someone to finance it, purchase inventory, rent a location, and open for business. And as the financial tide kept rising, operators of these marginal businesses were able to sell enough to stay in business.

And why not? Money and credit were not only easily obtained by business, but also by shoppers who bought stuff they didn’t need with money they didn’t have, just because they could.

And now comes the reckoning.

Three years ago when the economy was robust the companies which did the best job of marketing themselves doubled or tripled in size. Today, phenomenally successful marketers are working to repeat last year’s sales. Most companies are shrinking. And too many small businesses don’t even have a marketing program.

For operators who understand the minds of customers, we now live in a time of great opportunity. The loss of sales volume across both retail and service industries has taken a corresponding toll on the media. Today’s advertising prices are a bargain. For the first time in my experience, even the price of your Yellow Pages ad is now negotiable.

But, a great price on an individual ad doesn’t include meaningful content for it’s message. Messages which pulled well two and three years ago aren’t working any more. And a bargain price on an ad which says nothing salient is a shameful waste of money. Today’s most important question isn’t “Where should I advertise,” it’s “What do I say?”

Our handbag shop owner has noticed that business is off. Fewer people are buying, and she suspects that “advertising” might solve her problem, but she has no understanding of how it works. In her ignorance she’s asking questions as silly as the “what do groceries cost?” dialog above. She has no plan. She doesn’t even have a goal. Worse yet, she doesn’t understand why either is necessary.

My prediction? She’ll waste a couple of grand trying to make customers do what she wants them to do, rather than providing what those customers want. Her store will fight to stay open through forth quarter of this year, hoping to pick up some big sales for Christmas. Those sales will not happen. Following a liquidation sale in January her store will close, permanently.

It’s not the bad operators that I worry about.

It’s the under capitalized, non-niched, owner operated small retail or service businesses. The companies which deliver real value for their customers, but haven’t created a marketable position for themselves.

Too many of these operators will effectively become twenty-first century sharecroppers. One hundred years ago they’d have borrowed the money for seed. They’d have planted, and prayed for rain. They’d have worked long, hard hours hoping for a large enough harvest and a market price that would allow them to sell their crop, pay back the loan, and have enough left to feed the family the coming winter.

In a number of conversations with small businesses over the last week the theme which keeps repeating is “I need working capital. I need to be able to purchase inventory.” Credit lines have dried up, and these operators are hurting. Not because they’re bad operators, but because the rules of the game have changed. Assuming they find new sources of capital, there will be limits on how much they can borrow and how quickly it must be repaid.

Get used to the new rules. We won’t be going back.

What can we expect from these new rules?

Every economic downturn shakes out the poseurs, wipes out the frauds, and toughens the survivors. A few will adapt to the new marketplace reality, and thrive.

- Those who thrive are the operators who will learn which items to stock. They will meticulously keep an adequate inventory while simultaneously avoiding items which won’t quickly sell.

- They’ll keep a close eye on customer count, perhaps in increments as small as fifteen minutes, in order to hold labor costs in check.

- They’ll learn exactly who their customers are, and exactly what is important to them. Every advertising message will attract new customers and persuade existing customers to shop more.

Their companies will be smaller, leaner, and incredibly efficient. And their relationships with those customers will become much more personal.

Great companies are born of adversity. Are you ready for greatness? Shall we get started?

__________

Chuck McKay is a marketing consultant who helps customers discover you, and choose your business. Questions about effective advertising in this economy may be directed to ChuckMcKay@ChuckMcKayOnLine.com

One of the things guaranteed to make copywriters (and to a lesser extent media salespeople) groan is an advertiser who claims he needs to reach “everybody.”

One of the things guaranteed to make copywriters (and to a lesser extent media salespeople) groan is an advertiser who claims he needs to reach “everybody.”

No ad can possibly reach everybody. The human anatomy prevents it. If you have a minute, I shall happily explain why.

Amazingly, most people are not poised in front of their television sets breathlessly waiting to hear of an opportunity to dump the cash from their purses into Mr. Advertiser’s cash register.

Nope. Most people are instead attempting to ignore thousands of radio ads, e-mails, product placements, signs, newspaper and television ads, billboards, matchbook covers, calendars, and the odd Rubik’s Cube with some company’s logo on it.

Out of self defense, human brains are physiologically prevented from paying attention to things that don’t directly apply to them. And truthfully, most of what they see doesn’t apply.

What does apply to most people? Their kids, plans for the weekend, the empty box of corn flakes, remembering to program the TIVO, getting to the game on time, the in-laws coming to dinner, filing for an extension on the tax return, running late for work, or getting home before “Are You Smarter Than A Fifth Grader?”

They’re eager to find information which will solve their problems, and yet, they’re not paying attention. They see and hear advertising with their eyes and ears, but they don’t consciously notice those ads.

That’s because the human brain won’t let them. Again, let me explain.

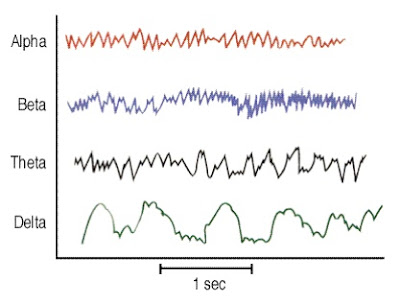

The synapses of the human brain fire at different rates during four different mental states. They are:

1) Delta – 0.5Hz to 4 Hz – Deep Sleep.

Delta waves trigger release of growth hormone, which helps the body to heal. This is one reason sleep is critical to the healing process.

Delta waves trigger release of growth hormone, which helps the body to heal. This is one reason sleep is critical to the healing process.

2) Theta – 4 Hz to 7 Hz – Drowsiness.

Theta states most frequently occur fleetingly as people pass from higher consciousness to deep sleep, or return from it. Theta waves occur during meditation, and have been linked to visual and emotional creativity.

3) Alpha – 8 Hz to 13 Hz – Relaxed.

The alpha state is a highly creative condition of relaxed consciousness. People in alpha state tend to recognize non-obvious relationships. Interestingly, it’s also the resonant frequency of the earth’s electromagnetic field.

4) Beta – 14 Hz to 30 Hz – Alert and focused.

The beta state is associated with peak concentration, heightened alertness, improved hand/eye coordination, and better visual acuity. During beta state new ideas and solutions to problems literally flash through the mind.

The higher frequencies represent more brain activity, and require greater energy consumption. Like every other part of the body, brain activity kicks into higher performance only as necessary. The more familiar the activity a person is engaged in, the less conscious activity is necessary.

Most of us have driven to work only to note upon arrival that we have no conscious memory of the trip. Individuals who drive a lot of highway miles frequently find themselves coming up with good ideas as they drive. Daydreaming while driving is an example of the brain in theta state. It’s easily induced by the hypnotic sameness of road markings and sounds.

As long as there are no surprises on the trip, driving to work can also easily produce an alpha state. The driver is relaxed, and the familiarity of the surroundings allow the driver to sing along with the radio, or listen to conversation without planning to respond.

But imagine the car in front of our driver slamming on the brakes. Our driver immediately transitions into a state of heightened awareness, faster reflexes, and instantaneous decision making. This is clearly a beta state of peak concentration.

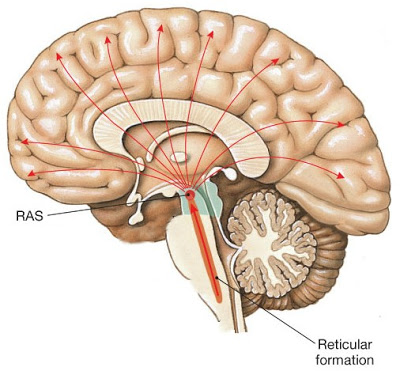

At the top of the brain stem, between the medulla oblongata and the midbrain is a collection of nerve fibers known as the ascending reticular formation. Activation of this reticular system is necessary for higher states of brain activity. Think of the reticular activating system as a sentry constantly looking out for conditions which require a conscious response. Anything important or relevant snaps the brain into higher states of consciousness, even from deep sleep.

At the top of the brain stem, between the medulla oblongata and the midbrain is a collection of nerve fibers known as the ascending reticular formation. Activation of this reticular system is necessary for higher states of brain activity. Think of the reticular activating system as a sentry constantly looking out for conditions which require a conscious response. Anything important or relevant snaps the brain into higher states of consciousness, even from deep sleep.

Anyone who’s moved to a home near the railroad tracks has been awakened by a train passing late at night… for the first few nights. While the loud noise is unusual and potentially threatening, the reticular system jerks the brain from deep delta sleep to beta wide awake consciousness. After a few days, when the experience becomes commonplace, the reticular system doesn’t even bother to activate, and the resident sleeps through the night.

Mothers recognize their child’s cry even in a room full of children. The reticular system catches the familiar tones of the child’s voice, activating a beta state in the mother.

And most of us have heard someone call our name in a crowd, only to discover that the caller was trying to catch the attention of someone else with the same name. The reticular system activates a beta state at recognition of the name, and de-activates for the brain to return to alpha mode once the mistake is obvious.

Newspaper readership increases with the addition of a photo, especially when it’s a picture of people. Why? Because the reticular activating system zeros in on other people, to see if they’re familiar.

Familiar is only one of the conditions the reticular system watches for. It is also ready to draw our attention to unusual, problematic, or threatening conditions. Any of these which appear to be important or relevant activate a beta state. If the conscious mind dismisses this “false beta” as not relevant, the brain returns to a lowered state of consciousness.

Can we plant a reticular activator to trigger a beta mode state at a later time? Yes, we can.

Embed a specific sound and get your listener to recall a whole series of emotions. Law and Order’s “Doink Doink” sound when the next scene starts. The sound of Pac Man wilting at the end of play. Duracell’s three tone logo. “You’ve got mail.”

Or embed a visual cue. Since 1997 Liberty Tax Service has done no advertising other than to place people in Statue of Liberty costumes on the street in front of the franchise. From roughly the first of the year until April 15th the Statue of Liberty costume serves as an activator, reinforcing Liberty’s function, as well as this location.

Here’s an interesting fact: the effect of advertising is greatest closest to the purchase. And if you think about it, that makes sense. Remember, a purchaser only buys when she feels the gap between what she has and what she wants. If she has an empty box of cornflakes, she’ll want more corn flakes. Once she’s become aware of her need for more flakes (by pouring the last of the old flakes from the box) she will also become more aware of corn flake advertising.

What a great time to present your message. Advertise your brand on television, or send her a letter, or show her a point of purchase display. Give her a compelling reason to choose your brand while her reticular system is most likely to bring your message to her conscious attention.

But how can you predict when that metaphorical box of flakes will go empty? Unless your business is seasonal, you can’t. And that pretty much means you need a constant presence in the marketplace.

We read from left to right, from top to bottom. The eye is drawn first to photographs and headlines, seeking, finding, and sorting through the information on the page. The reader scans in alpha state for anything familiar, unusual, problematic, or threatening. When one of those conditions is noted, the reticular activator pulls the readers attention to the words or pictures, and in beta state the conscious mind weighs the evidence.

We read from left to right, from top to bottom. The eye is drawn first to photographs and headlines, seeking, finding, and sorting through the information on the page. The reader scans in alpha state for anything familiar, unusual, problematic, or threatening. When one of those conditions is noted, the reticular activator pulls the readers attention to the words or pictures, and in beta state the conscious mind weighs the evidence.

It makes no difference whether the reader is considering news stories or advertising. If further examination reinforces the condition, the reader is engaged and stays in beta state. When the content has been read, the scan through the paper continues with the reader back in alpha mode, ignoring most of what he sees.

And though the consumption pattern may differ from left to right, top to bottom, this is how we use all media. People watching TV, listening to radio, or driving past outdoor ads will switch from alpha to beta modes and back as the content triggers the reticular activating system, and is accepted or rejected by the conscious mind.

Your corn flake ad will scream for the attention of someone who’s out of corn flakes. The rest of the readers / listeners / viewers (those who don’t have an empty box, as well as those who just do not like corn flakes) will either note the ad and quickly return to alpha state, or ignore it all together.

Got it? You’ll never reach everyone with any ad. We don’t all run out of cornflakes at the same time.

Whether it’s corn flakes, or worms, we want to keep the bait relevent when we’re fishing for customers.

Your Guide,

Chuck McKay

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Your Fishing for Customers guide, Chuck McKay, gets people to buy more of what you sell.

Got questions about moving your shoppers into a beta state? Drop Chuck a note at ChuckMcKay@FishingforCustomers.com. Or call him at 760-813-5474.